Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

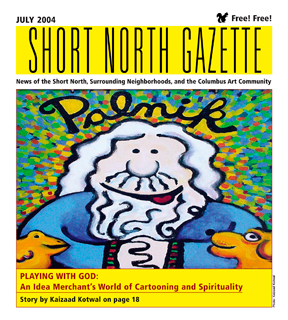

Playing with God

An Idea Merchant's World of Cartooning and Spirituality

By Kaizaad Kotwal

July 2004 Issue

Return to Homepage

Return to Features Index

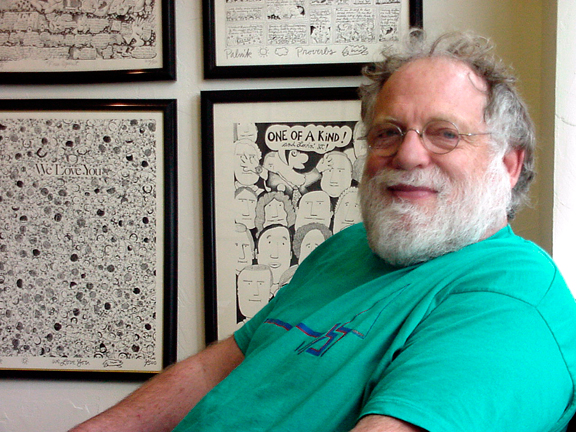

Paul Panik, living witih kindness in the present. © Photo | Kaizaad Kotwal, 2004 In this post-9/11 era, we face questions about laughter in the face of tragedy: How soon is too soon to laugh? Who and what are appropriate subjects for satirical skewering? Does the revered, yet often threatened, First Amendment protect all expressions of humor?

Cartoonist and artist Paul Palnik may not worry about such issues because his work is deeply rooted in a spiritual quest for what makes humanity so blessed and blemished all at once. I sat down with Palnik in his new studio at 14 East Lincoln Street in the Short North to talk about his art, his life and his relationship with God.

Palnik, who refers to himself as a prankster, has a mischievous glint in his eyes and a playful demeanor. With his white beard he looks a bit like a stereotypical vision of the big guy in the sky.

Born in Cleveland, Palnik was raised in Cleveland Heights and at 58 finds himself settled in Columbus. He recently started to trace the roots of his Jewish heritage and found that his great- great grandparents were of Lithuanian, Polish and Russian extraction. “I am a third-generation Jewish-American,” he says with pride.

Palnik refers to Columbus as his personal home and Cleveland as his biological one. In this city, Palnik lives with his wife Nancy, a nurse administrator at the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital. They have three sons, aged 33, 21 and 18, and a daughter, 16. Before settling in Columbus, Palnik spent a year in Florida and a year in Jerusalem.

Palnik first encountered Columbus in the 1960s, when at the age of 17 he came to Ohio State University to study drawing and graphics. In addition to the turmoil in Vietnam, that was the age in which pop art was beginning to make its presence felt and legitimized through the work of luminaries like Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns and Ohio State’s own Roy Lichtenstein. In fact, Lichtenstein and Palnik shared a mentor in artist and professor Sidney Chafetz. Both men influenced him and his work greatly, Palnik says.

I ask Palnik what made him choose his career path and he replies: “It was chosen for me by the Almighty. You ever hear the cliché ‘he was born to do this’? Well, that’s me.”

Palnik recalls how there never was a time when he wasn’t drawing. “My mother was an artist and when I was a toddler she would give me huge sheets of brown wrapping paper that our laundry came in and hand me paints and pencils. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t draw. I grew up thinking that is what all people do.”

When I ask Palnik what made him choose cartooning as his art form, he connects the dots back to his working-class background. “Cartooning was a conscious choice for me,” he says, “because contrary to the stereotype that all Jews are rich, we came from working-class people and were always very conscious of what we could afford and what we couldn’t. I wanted to do serious art but art that was for the working person,” he adds. Palnik believes much of the art world today is inebriated with elitism and aloofness and neglects the needs of the not-so-rich.

“Being a bit of a prankster and having a strain of the standup comic made cartooning a natural choice,” he says. Besides, Columbus and Ohio State have a long tradition of producing cartoonists and humorists, from James Thurber to Roy Lichtenstein. The university also houses the largest collection of cartoon art in the United States.

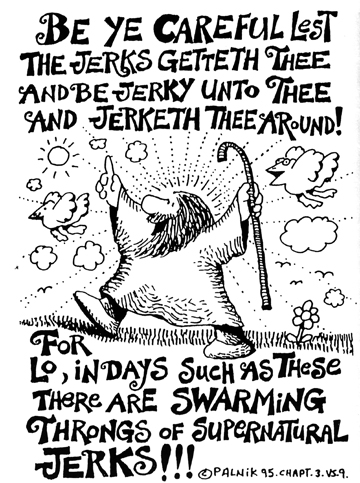

When you look at Palnik’s creations there is a quirky playfulness in them, both in style and content. Many of his works are extremely detailed and visually complex, almost meditative in their quality, asking viewers to go on a journey following the complex lines and the even more complex rhythm of ideas embedded in them. His works remind me of Buddhist mandala paintings where the creation and appreciation of the artistry are deeply rooted in meditative qualities.

Palnik says the content that he is drawn to concerns spiritual matters, freedom of the soul and the human urge for individuation. He believes much of what passes for humor these days relies too heavily on the sexual and the violent. He likes to raise his work out of the mundane and into something higher.

I ask him whether superhero cartooning like the X-Men can justify violence, because the ultimate goal of that gang of superheroes is to vanquish evil and those who treat outsiders with contempt. Palnik agrees, then adds, “Defending good doesn’t give you a license to do violent things.”

Much of Palnik’s work ethic and philosophy comes from being Jewish, which he calls a way of life. I ask him to explain what that means to him and how it manifests itself in his work. “Well, I have a soul, and it doesn’t have a beginning and an ending, and I like to let it go free,” he says. “I believe in God, a soul, my heart, kindness and goodness.”

He refers to himself as a practicing Jew and defines that as “living with kindness, living in the present.” Palnik goes to synagogue regularly but says his children do not practice their religion as much as he’d like. Palnik and his wife have always encouraged their children to be exactly who they are because he believes that will allow them to be deeper individuals.

I ask Palnik what draws him to spirituality time and again as a human being, as a Jew and as an artist. “I like to play with God,” he says, very matter-of-factly. “There’s this concept that some people are at a distance from God, but we are very close together and I play with him. God is in the pen, in the ink, in the people who read my work.”

I am curious if Palnik has always believed in this way of relating to God. “It was instinctive for me, but it took me a while to articulate it,” he says.

Palnik believes he has a gift that allows him to play with lofty concepts in a non-mocking way. The concepts he refers to are ideas of life and spirituality that he has found in Judaism, in the Bible, in the Hindu Upanishads and in other great books and great lives through the ages. “I am a mystic,” he says with a glint of mischief in his eyes.

© Paul Palnik I probe further to see what Palnik’s concept of God looks like. “God is God,” he says. “I have traveled the world and have met people who are awake and people who are not awake to God. And God transcends states, religions and boundaries.”

It is obvious that Palnik is a critical thinker. By nature and by virtue of his profession he is more keyed into the ways in which the world bumbles and tumbles along. I ask Palnik what current issues trouble him as a social critic and an artist.

“I get incredibly saddened by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” he answers. “I remember I used to be able to go anywhere in Israel, from Jerusalem to Arab towns. I have seen the people there live peacefully side-by-side. I used to sit and have tea with an Arab merchant, but now I can’t even go to my favorite restaurants.”

I ask him whom he holds responsible for the deterioration of the situation. “Arafat,” he replies. “He refused to share.” After further prodding about Israeli complicity in the deterioration of the situation, he says, “Yes, I suppose, there are equal counterparts.”

I ask what he would he do if he were given charge of the situation. “I know I could do it,” he says. “You have to take geography out of the equation and start to think outside the box. When they let me run the show I would clean up the whole place. I could run the whole world,” he says with a naughty laugh.

Putting on his more serious face again he starts to chat about other things that rouse his soul and his cartoonist’s pen. “I hate arrogance,” he says. “The arrogance of wealth and power.” Palnik admits that sometimes pondering the state of the world and humanity can be an exercise in feeling one’s power diminish exponentially. So he turns to his work to empower himself. “I know that my work has affected thousands of people, making them feel better, making them laugh, making them think,” he says.

I ask Palnik what he might have become if cartooning and art had not overtaken his passions by storm. “A rabbi,” he says. “It’s that God thing again. God is very real to me. He is the eternal creative presence. He pervades everything. He is the now of now. He is the soul of now.”

Speaking of his creative process, Palnik says he is always observant, reads the papers and keeps his eyes open. He believes life is made up of the remarkably absurd and the profoundly meaningful. He says he likes to juxtapose those elements to find the humor and spiritual resonance in the human condition.

Palnik works on several pieces at once. Each takes him roughly six weeks to finish from beginning to end. “I like to leave in the mistakes,” he says, referring to the fact that he never does rough sketches or several versions before finalizing a work. “This retains more of the human factor,” he says.

When it comes to the issue of color versus black and white, Palnik says that because he is an idea merchant his work is more lucid in black and white. “Color just raises the price and is about visual titillation,” he says. Since so much of Palnik’s work explores the dualities of the world, black and white works in a substantive and contextual way that color would not.

Palnik’s work is imbued with a sense of detail and metaphor that obviously emerges from a close scrutiny of the churning of the universe and that foible-ridden species called Homo sapiens. His prints are available at his studio in the Short North and you can get a book of his work titled Eternaloons. As a man and an artist who shuns violence, Palnik’s work embodies the truism that the pen is mightier than the sword – and infinitely funnier.VISIT HIS WEBSITE AND FACEBOOK PAGE (THE WISDOM OF CREATIVITY)

www.1800cartoon.com • www.facebook.com/thewisdomofcreativity

© 2004-2013 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com