Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.comElijah Pierce, Ecclesiastical Artist

By Betty Garrett Deeds

February 2003 IssueReturn to Homepage

Return to Features Index"And whatsoever mine eyes desired I kept not from them, I withheld not my heart from any joy; for my heart rejoiced in all my labour: and this was my portion of all my labour." – Ecclesiastes 2:10

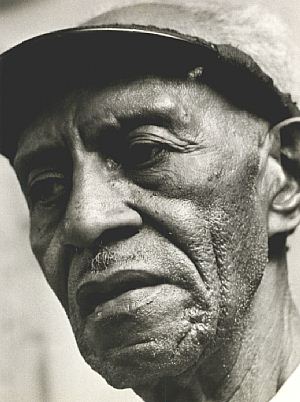

Elijah Pierce (1971 photo © Dick Garrett) On March 5, 1892, Elijah Pierce, the son of a slave, was born on a cotton farm in Baldwyn, Mississippi. He described his father as "a thoroughbred farmer who believed in growing his food." But Elijah wasn't born to work the fields: "My two brothers liked to farm, but I didn't. Guess I was peculiar. I didn't like to play with other boys. I liked the woods. I would go there with my dogs and my pocket knives."

His father gave him his first pocket knife early, and by the time he was seven, an uncle had instructed him in the best kinds of wood to use from what could be found on the forest floor and taught him how to carve simple little wooden farm animals. Pierce also recalled, "When I'd find a smooth-bark tree, I'd carve on it – Indians or an arrow and heart or a girl's name – whatever I thought of."

Not tied to the land as his father and brothers were, he "always wanted to travel the world from place to place." As a teenager, he hung around the local barbershop in Baldwyn and learned how to make a living from the trade. But he had restless feet and a traveling mind and also hitched rides on trains and worked at transient jobs for railroads.

"About 1912, best I can remember, I got off a train and saw a straight hickory stick by the side of the road. I liked it, cut it down and carved a cane. It's the first thing I can remember carving besides the trees at home."

Pierce would return home to visit his mother, who encouraged his religious leanings as well as his barber's work. He needed that strength when Zetta Palm, the woman he had married, died in 1915 after giving birth to a son, Will. "In 1920, he received a preacher's license from the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Baldwyn.

By this time, the adult Pierce was 6' 2" with the regal bearing of both a Masai warrior and an Old Testament King. There was a sculpted quality about his body and bearing, and he drew the admiration of many young women he met as he traveled the country, stopping from time to time to barber again.

It was in Chicago that he met a young woman from Columbus, Cornelia Houeston, who made him reconsider the virtues of being footloose. "I said I'd never marry (again) ... but one day I told the man I worked for to find another barber, and I got on a train to Columbus."

Apparently he signaled his intentions ahead. In September, 1923, "When I got here, she spoke to me like I'd just been down the street. 'Oh, good morning, Elijah, how are you?' I said I'd decided to marry her after all. She thought awhile, then said, 'Put on your hat then, and let's go down to the courthouse.'"

Pierce always chuckled with deep satisfaction when he recalled that after they married, "that Nigra woman finally kissed me and said, 'Now you're mine and I'm yours.' We went back to her house, and she said, 'Don't you want a bath to wash that Illinois dirt off you?'"

"I didn't," he confessed, "but seemed like she was gonna be the boss, so I did. She got a brush and went to scrubbin' my neck. Hooey! I thought I was ruined. But that woman was a lifesaver. She had more sense than me. Then on, everything I put my hands on turned to work and money."

"I never had $1000 cash in my life till I found she saved it from what I gave her by the week (as a barber). Had it in teacups and pots and tied up in hankychiefs, and one day rolled it out on the bed and showed me."

"I'd been shootin' pool and stuff with the fellas, but after that, I helped her save the second thousand." We stayed together 33 years and bought this place (the shop on East Long Street) and a brick house. I tell you, there ain't nothin' in the world any better than a good woman and nothin' any worse than a bad one."

During the '20s, Cornelia "saw a little elephant and liked it, so I carved her one like it for Christmas. She put it on a chain around her neck. I said, 'You like that thing that well, I'll carve you a zoo.' And I did. Then fellas would come in to the barber shop and say, 'Can you carve such and such a animal?' or some other thing, and I'd try that."

In the intervals when no customer was occupying his barber chairs, he sat on a Victorian straight-back chair and carved the increasing range of his visions of daily American life with figures from his black heritage. They ranged from his first car, "a coupe that made me feel like a airplane," Joe Louis and Marian Anderson, and his own version of Alexander Hamilton's mansion, which he had once visited and greatly admired.

He built a miniature duplicate of it and filled it with carved chandeliers, mantels and rocking chairs, filling the rooms with such diverse figures as a black lady with one shoe off, "under the influence, you might say."

Aside from his uncle's early basic pointers, Pierce never had training. Asked what he worked with, he explained, "A pocket knife mostly ... this twin Hinkle. I gave $16.54 for it, it's German and it's the best ever made. I also use a chisel, a piece of broken glass to cut things down, and sandpaper. Those are my tools. When I'm done carving, I use paint, shellac and polish to make the work stand out." Hair tonic and the tools of his barber's skills filled the shelves alongside them.

During the Depression, Elijah traveled around to fairs and exhibits and sold a few figures, but gave away most of them as "little souvenirs" for friends and customers, who, in turn, would bring him pieces of wood for carving material.

About this time, the man who was a licensed Baptist minister but had repressed his "calling to preach" for some 20 years, became obsessed with his childhood religious teachings. He began to carve his versions of the Garden of Eden in 1929, then Noah's Ark, peopling them with primitive figures of his choice, often "preaching a couple of sermons and talking about them as they came to me."

He also began mounting his three-dimensional figures on cardboard and wooden backgrounds, and with this technique compiled a personal vision of the New Testament which he called simply "The Book of Wood." Completed in 1932, it comprised seven enormous "pages" with 33 bas-relief carvings delineating scenes of "highlights from the 33 years of Jesus' life."

The images have a mystical eloquence, depicting such objects as a Rose of Sharon floating over Jesus healing a mass of "the sick, the lame and the halt." Jesus' skin is black in some of the figures, but Elijah eschewed social commentary, saying merely, "It's in the grain of the wood." Sometimes Pierce and his wife conducted "sacred art demonstrations" to explain the meanings of the Book's contents to visitors. Occasionally, the barber/preacher conceded to feeling some regret at the lack of recognition given his sculpting, and especially his "failure to preach and heal the sick and be a great man for my country and my race." However, it could truly be said that he was following his calling as a preacher while pursuing his artistic visions. Between haircuts.

There were a few newspaper articles about him in the '40s, some by the late Citizen-Journal columnist Ben Hayes, who often shook his head sardonically at the irony of Elijah's practicing his art "only a block away" from the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, which was either unaware of or unheeding of the greatness so near it.

The only exhibits Elijah held were in churches, and he claimed to "give little thought" to what would come of his efforts. "I enjoy this for the work of it." That alone, along with the devotion of Cornelia through 33 years of marriage until her death of cancer in 1948, sustained his artistic drive.

In 1952, he married another remarkable lady named Estelle Greene, whom he described as "my kinky-headed woman. I say she ain't worth a dime, but I wouldn't take a thousand for her."

Although he continued working in his barbershop at 483 E. Long Street for decades, Estelle also encouraged him to grow as an artist and a lay minister. However, it was not until the early '70s, by which time he was using one room at 534 E. Long Street for his barber's work and another at the east corner of Emmett Alley to store his carvings, that decades of public unawareness of his other work gave way to small but crucial recognition that a great folk artist was working here in Columbus.

In 1970 or 1971, Pierce's carvings were entered in a Golden Age Hobby Show, sponsored by the now vanished Columbus Citizen-Journal, at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, a block away from Pierce's own stations at the cross, so to speak, and the red and white striped barber pole depicting his known profession..

Boris Gruenwald, a Yugoslavian graduate student in sculpture at Ohio State University, saw them there or at a YMCA exhibition and said "this work had to be where people could see it," Pierce explained simply. "That was real nice of him." They became close, lifelong friends. Through Gruenwald's influence, an exhibit of Elijah's art was staged at OSU's Hopkins Hall in 1971. On posters outside, for the first time, he was labeled ELIJAH PIERCE, FOLK ARTIST.

Sculptor Frank Gallo, whose work had been featured on the cover of Time Magazine, was then a visiting artist at OSU, and when he saw the show there, remarked, "Beside him (Pierce), I feel like a poseur, an imitator. He is motivated solely by love for what he does, and his work has both naivete and a deep understanding of his subjects." He arranged to have 76 of Elijah's creations exhibited at the University of Illinois in December, 1971.

At the time, Pierce marveled, "These teachers at the university kept on askin' how I can carve. And I told them, that's just how things are shown to me. God guides the hands."

Whatever one does or doesn't believe about the guidance of events, the seeds of Elijah Pierce's talent-sprung from the earth of that Mississippi cotton farm in the previous century - blossomed after those breakthrough showings in 1971. It was as if the Red Sea parted, and people suddenly gained wide access to the folk artist's long-hidden talents.

His work was shown at the Bernard Danenberg Galleries and other elite venues in New York shortly after the University of Illinois exhibit, and then, in February, 1972, at the prestigious Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Critics hailed and hosannaed the talents of the newly found artist, Elijah Pierce, then 80.

"Was that show in New York exciting?" Pierce echoed someone's question. "Oh, wasn't it! We had tickets on TWA paid for and all, and oh honey, we had a party. It was swell. They treated us as white and nice as Mr. Nixon. After the show, there were nearly 1000 people in a big room, all them artists and celebrities had seen the work and welcomed me and said such nice things. People shook my hand till it cramped. I had to punch my wife in the ribs a little and ask, 'They talkin' about me?'"

Finally, in November, 1972, Pierce's carvings and sculptures were exhibited at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts. Mahonri Sharp Young, then CGFA Director, made this astute observation: "You can always go over to Elijah Pierce's barber shop on Long Street and see for yourself that everything [he does] is absolutely real. Long Street is the 125th St. of Columbus, but there is not that much bustle. Mr. Pierce did not learn his work from us or anyone else. He used to set up his wares at country fairs, and, in a way, he still does; he is a preacher, and he likes to talk about his vivid carvings (and) their meaning for him. On one side of the highway you find love, peace, happiness, home, content and success: on the other, confusion, woe, pain and hell house. Your life is a book, and every day a page."

In 1973, Pierce won first prize at the International Meeting of Naïve Art in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, and other great honors paved the way to his receiving a 1982 award from the National Endowment for the Arts' National Heritage Fellowship as one of 15 master traditional artists.

A sculpted monument to perseverance, he is now a prophet who is honored in his own land. From the current CGFA permanent collection of about 300 of his sculptures and paintings to an Elijah Pierce collection permanently housed at The Martin Luther King Center here, his creations can be appreciated by and an inspiration to uncounted generations of Columbus people yet to be born.

The belated acclaim from intelligentsia who verified his being a "genuine folk artist" gave him tremendous joy, but he also noted without rancor: "For 30 or 40 years, only a few of your people (whites) knew about me. Now I know the joy of making other people happy. The Good Lord has blessed me. People are calling me a celebrity, but the Bible says you have to humble yourself to be exalted. I'm just the same old Elijah Pierce."

But in a conversation with a friend not long before his death on May 7, 1984, at the age of 92, he laughed slyly, "You know, I'm famous now." The laughter grew in both. "If I'd a known this all those years ago, I woulda bought a bigger hat."

He never did, though. In private, he hewed to his eyeshade, which enabled light to focus more directly on the visions which took shape before him.

Elijah Pierce, the barber and the preacher, knew the truth of Ecclesiastes 3:1,2: To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted.

© 2003 - 2018 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Features IndexReturn to Homepage www.shortnorth.com