Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Ralph Whitlock began contributing his country columns to the British Guardian Weekly in 1981 after an already extensive literary career

and continued until his death in 1995 at the age of 81. He was considered one of the most popular writers the Guardian ever had.

(Some editing to American spelling may have occurred in our hard copy version reprint in the Short North Gazette.)

About Ralph WhitlockTinged with Sepia

by Ralph Whitlock

January/February 2020 Issue

Guardian Weekly May 9, 1993

I have just been enjoying a rare treat – a visit from a 26-year-old Californian grandson whom I had not seen for 12 years. We rejoiced in the sunshine, which enabled him to make a pilgrimage to many of the places where his ancestors lived, but a rare rainy evening inspired us to bring out an old family photograph album. What a treasure it is!

Our oldest album dates from the 1860s. It must, for it features my paternal grandparents on their wedding day, which I believe was in 1868. There is a picture of my maternal grandmother in the 1890s and an older one of her mother in mid-Victorian costume. These portraits take us back nearly to the beginning of photography, for William Henry Fox Talbot, the father of photography, was born at Lacock Abbey in the year 1800 and started his investigations into what one contemporary encyclopedia happily terms “the fixing of shadows” in 1833. The Royal Society presented him with a medal for his work in 1842. So when my grandfather and grandmother were married the youthful art was then only about 30 years old.

Their wedding picture is obviously a studio affair. Grandmother is sitting bolt upright while an ill-at-ease grandfather stands beside her in a formal attitude, one hand resting lightly on the back of her chair. The photograph of my great-grandmother, taken at about the same time, reveals similar careful posing, as for an oil painting.

Those of the 1880s and 1890s are likewise all studio efforts, but by the turn of the century, although still posed, the subjects are taken against their own background. They arrange themselves in family groups in the garden, or pose bytheir front doors. Here is one of ten persons – six men and four women taken around the year 1900, I would judge; and the interesting feature is that five of the men (though none of the women, of course) are smoking cigarettes. And here is another, of my father’s cousin, dating from about 1895. The young man, then about 20, is posed with his bicycle, against a studio background. The significant feature is the bike, which was then such a novelty as to be thought worth a studio picture. He and my father were the first persons in our village to own bicycles, so recent is the innovation.

In the studio portraits of children the youngsters have invariably been overdressed for the occasion, especially in the more affluent Edwardian days. In one of some cousins of mine of that time the babies wear unbelievably elaborate bones, lace collars, fur capes and fur scarves.

In earlier and presumably more stringent times the dresses are plainer. Nearly all the women and girls, even the quite tiny ones, have high collars, Chinese cheongsam-style, and the dresses have a line of thickly studded buttons down the front. In Edwardian photographs, too, sailor suits are popular for little boys.

After the World War I things become much more free and easy. The era of the Brownie camera has arrived, and snapshots show people doing things other than posing. I have a lot of photographs of farm men about their accustomed tasks, working, of course, with horses. From a family point of view, though, there is a lot of interest in the more formal pictures of schools, sports clubs and Sunday school outings.

However, the quality has deteriorated as the quantity has increased. The early photographs, as I suppose one might expect from studio studies, are of excellent quality, most of them turned to a shade of sepia but still clear and sharply defined, after 90 years and more. The more recent ones are also quite good, depending on the skill of the photographer, but those of the 1920s and 1930s have, on the whole, faded quite badly. This particularly applies to the home-processed ones. A cousin of mine who lived with us in the 1920s was a keen amateur photographer, spending hours developing and printing his photos in a little room at the back of the house, but the copies I have are now faded almost past recognition. Which is a pity, for some of his subjects are of Egyptian scenes, taken when he was in the army.

Incidentally, in the Edwardian sections of my albums I notice a cult of using photographs as Christmas Cards. Here, for instance, is a Christmas card, featuring, of all places, Barnes Station! And many of the pictures of places seem strangely empty. In a photograph of Wherewell, Hants, 10 little children and a dog are playing in the middle of a village street. It fills me with nostalgia for the spacious days when children and dogs could play unhindered by fear of being cut off by a speeding car.

Coming to the Aid of the Injured Party

by Ralph Whitlock

March/April 2019 Issue

Guardian Weekly, November 3, 1991

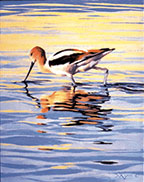

Drawing © Roger Pearce A Saskatchewan reader expresses interest in my recent article on birds and animals that tolerate each others presence but then asks, “Have you ever known one species come to the aid of another?” He then proceeds to give a remarkable instance of this:

“Before coming to Saskatchewan, I lived in Hamilton, Ontario, on the western point of Lake Ontario, in the end suite on the fourth floor of an apartment. Immediately off the balcony stands a tall poplar tree in which nest a pair of Baltimore orioles, a beautiful bird with a lovely song. High above the ground, they were at the height of my balcony. I looked for their return every year and watched them nesting only a few yards away.

“One afternoon I heard them making a terrific din, far removed from their usual warble. I went out on the balcony and saw the pair frantically dive-bombing a large black squirrel which was making its way up the tree towards their nest. It ignored their harsh cries and their wings as they swooped and struck at its head. Their cries grew more strident as the squirrels got to within a couple of feet of their nest.

“I had reached for an empty flower-pot to throw at the squirrel when I was astonished at what happened next. Down at ground level, extending out from the back of the building, is a roof which covers the parking area. It is not a closed area, for the sides are open, and it shelters several dozen common English sparrows, which nest in the rafters, feed on the ground, and very rarely ever fly higher than the roof. To my amazement, a squadron of seventeen sparrows suddenly flew out from under the roof – I counted them – and rose straight in a body to my end of the roof, now circling. They flew in formation directly to the poplar tree, where they immediately began to dive-bomb the squirrel, in groups of two or three, one after the other.

“The squirrel kept going but could not resist so sustained an attack and, after a couple of minutes, turned tail and beat it down the tree. Once he began to flee the sparrows regrouped in the air. They did not light in the tree but flew straight back down to the parking area and disappeared under it. The exhausted orioles then disappeared into their nest and did not emerge for an hour or so.

“Their distress call is certainly far removed from their song. I heard it while inside the apartment, recognised it as something wrong, and went out to investigate. But have you ever heard of one species of bird responding to the distress cry of another?”

No, I don't think I ever have, though I think that it happens with certain com-munal-nesting sea birds. For instance, let a predatory skua gull appear in the middle of a nesting colony of terns and I imagine the entire colony would take alarm, regardless of which species of tern was immediately threatened. However, the nearest parallel that I have come across concerns a dog and a cat of my acquaintance. I believe I may have related it before, but it will bear repetition.

Some years ago I sold a house in which I had been living, and, as the new resident was a relation of ours, we decided to leave our cat behind. They had a dog, but the dog had been used to living with a cat and the cat had been living with our dog, so each was used to sharing quarters. As a matter of fact, they settled down quite amicably and took very little notice of each other.

About a week after the move a big dog came into the garden from next door and, finding a strange dog in residence, pitched into it. An almighty rumpus ensued and people came running. So did the cat. Spitting and with talons extended, she made straight for the intruder and, before anyone else could act, landed on his back. The boxer, disconcerted, left attacking the dog and fled back to his own territory, the cat in hot pursuit. It never ventured into the garden again. The newly resident dog retired to the kitchen and remained there, cowering, for an hour or two; the cat proceeded to wash herself.

Now the more you think about this the odder it seems. Here was a cat answering a cry for help not only from an animal of another species but for help against an animal of the same species as was being attacked. If it had been two cats ganging up against a dog it would at least have been logical. And the fact that the dog and cat concerned had been living together for only just over a week makes the incident all the more remarkable. Clearly the bond between the cat and the dog was their home; each had accepted that the other had come to share it and resented the intruder.

Come to think of it, the most fertile source of examples of animals reacting in defiance of the species instinct is when one of the species is human. From the days of Romulus and Remus, fostered by a she-wolf, to dolphins that deliberately play with humans and rescue them if they get into difficulties, instances abound. Pumas are credited with saving the lives of lost children; films of sea lions in the Galapagos Islands show the animals enjoying a frolic with humans; examples are known of deer soliciting the aid of humans in freeing their young from a snare.

In a perfect world in which mutual trust prevailed there would be many similar instances of humans using their superior technical abilities to rescue our fellow creatures from scrapes into which they had been tempted.Can Spring Be Far Behind

by Ralph Whitlock

January/February 2019 Issue

Guardian Weekly, January 20, 1985

Harsh “chukk-chukka” cries from black-and-white birds drifting distantly against the grey sky were the first evidence we had last November of the arrival of the fieldfares. Now, tamed to some extent by frost and hunger, we watch them, as chestnut-and-grey rather than black-and-white birds, feeding on apples in the orchard. Deer venture into the swede field just down the road, and the garden has filled up with tits, robins, chaffinches, greenfinches, blackbirds and other small birds which, when the autumn woods were replete with food, were consipicuously absent.

I am weary of winter and its dark days. Last summer, warm and dry though it was, passed all too quickly. And too soon we had entered the diminishing days of autumn. By November we were having to cope with sunrise at eight and sunset at four, or thereabouts, and on cloudy days only a half-light even at mid-day. Christmas was a welcome relief, a chance to forget momentarily the prevailing gloom, but here in January we are no more than half-way through the domain of winter. Winter proverbs and maxims emphasize the fact:As the day lengthens /

So the cold strengthensOne warns,

On your farm on Candlemas Day

Should be half the straw and

two-thirds the hay.By Candlemas Day, February 2, the hungriest months of the winter are still ahead. There will be little grazing in the fields until the beginning of May – another three months at least. So the short days and the long nights drag on. English farms spend five hectic months of summer trying to grow enough food to keep their livestock alive during the other seven months. And the Scilly Islanders reap a rich winter harvest by catering, through their lovely fragrant flowers, for our longing for a glimpse of color and a breath of spring.

I often yearned to escape from the winter, and one year I did so. My wife and I flew out to Nairobi on the day before Christmas Eve and arrived back at Heathrow on the day before Good Friday. In the interval we had travelled right across Africa and along the west coast to The Gambia.

On Boxing Day we were on a safari in Kenya. At the end of January we were camping under palm trees by the Indian Ocean. We had adventures, not to be related here, in the bush country of Nigeria, Dahomey and Sierra Leone. Late February saw us a hundred miles or so up the River Gambia revelling in the abundance and beauty of the bird life there.

What a paradise for birds that is! The local birds are driven back to the river by the drought which is absolute all through the winter months, and there they mingle with innumerable visitors from Europe, refugees from the European winter. Swifts, warblers, and wagtails, fuelling up for their marathon journey to the north, are eclipsed by the scintillating bee-eaters, rollers, paradise flycatchers, bushshrikes, kingfishers and various storks, spoonbills, herons and ibises.

Travelling home via the Canaries, we made a detour to southern Spain, where we spent a fortnight with a daughter and her family who were then living near Malaga. From the clifftops overlooking the Mediterranean we saw the swifts again, and this time the swallows and martins, flying strongly in from sea. We heard cuckoos calling in the olive groves and watched hoopoes displaying around old, dilapidated farm buildings. Oleanders and mimosa were in bloom, and one day, on wasteland near the cliff, I came across a colony of spider orchids in full bloom, as they would be in Dorset in May.

Back in England, we arrived to clear, chilly weather and a sky so pale by contrast with the vivid blue we had been used to. As usual at Easter we went walking in the woods with our grandchildren and were pleased at their delight at finding the first primroses and sweet-scented violets. The church was decorated not only with daffodils and narcissi (sent up from Cornwall, for it was too early for the local ones to be in bloom) but also with branches of pussy willow, or sallow, or “palm” to us northerners, who seldom if ever see real palm and so substitute our willows for Palm Sunday displays.

Everyone was happy about the return of spring. “It’s come early this year,” they said. And the farmers cast a cheerful eye over verdurous grassfields and calculated how soon they would be able to turn out their cattle for an early bite. But to us the weather was cold and the countryside cheerless and bleak.

Then we realized what had happened. To appreciate an English spring you need to live through an English winter. And we had escaped the winter. Well, it was one of the things I had long dreamt about doing. One of them.

A book which I was given to read when I was a boy made a considerable impression on me. Entitled By Log Cabin and Camp Fire or something like that, it was an account of a missionary’s life in northern Canada. I revelled in the descriptions of journeys on snowshoes and by dog sleigh across the sparkling snow, to the wavering illuminations of the Northern Lights. I was enthralled by the migrations of the caribou, by encounters with wolves and polar bears, by the technique of spearing seals through blowholes in the ice.

But more than anything, though, I was attracted by the coming of spring. A dramatic event, when the weather suddenly turned many degrees warmer in a southern wind and the geese came flying overhead on their way to the tundra. Then the snow began to melt and water to collect in pools on the surface of the ice. Came a day when with explosions like thunder the ice on the frozen rivers broke up and the water started to flow again in frothing, clashing turbulence. Myriads of singing birds from the south would repopulate the woods, and the northern flowers would hasten to expand for their brief season of glory.

One year, I promised myself, I would spend a winter in the northern Canadian wilderness, just to participate in the stupendous triumph of spring. But I never have, and now I doubt whether I ever shall.

After our experiences of an African winter, though, it came to me that I needn't bother. All my previous life I had lived in a northern climate and experienced both a northern winter and the exhilaration of a northern spring, and I hadn’t realized it. So now I appreciate to the full the first signs of the inevitable awakening.

The hazel catkins are already shaking their pollen in the January woods. On mild mornings the song-thrushes are singing. Soon they will be joined by the chaffinches, the blackbirds and the skylarks. The redwings and fieldfares, resplendent in their new spring plumage, will be on their way back to Norway. In the garden, bulbs are thrusting their green spears sunwards, and very soon I shall have to be busy sowing seeds in the greenhouse.

When is the best season to take an overseas holiday in the sun? I don't know, and I don't mind if I never have another. Whenever you leave England you miss so much. Even in winter.

Animal Idiosyncrasies

by Ralph Whitlock

November/December 2018 Issue

Guardian Weekly, November 15, 1992

Intrigued by my recent article in praise of crows, several readers have written to me giving parallel instances of intelligent behaviour by them. I quote one from Canada, from a lady who lives by a six-mile-long lake on which she often goes canoeing with her husband.

“One afternoon we were paddling along,” she writes, “when we heard the greatest cacophony of crows. We angled over towards the sound but kept a discreet distance so as not to disturb the birds. I trained my binoculars on them.

“About 30 to 35 crows were gathered in a big tree at the edge of the water. Down at the waterline were some rocks, jutting out into the lake, and on these were about six of the crows, bathing. And, as I watched, I could see that they were taking it in turns!

“As each crow finished its ablutions it hopped up on to a branch and its place was immediately taken by another, yet there were never more than about six in the water at once. Those up aloft seemed to be doing two things, namely guarding the bathers and shouting encouragement.

“On another occasion, in the winter of 1990, I walked for 50 yards or so on the ice covering our lake and deposited there a dead squirrel recently killed by a car. The next day two crows turned up. It took them ages to investigate. One would sidle up to the carcass and start to peck at it, while the other stood some distance away. Then the first bird would fly up and alight on the ice, leaving the second bird to have a go. It approached the carcass very circumspectly and took ages before it attempted to take a bite. Then I noticed a third bird high up in a tree, simply watching.

“It took the crows four days to eat the squirrel. At no time did I see a bird on the ice without another in the high look-out perch on the tree, and at no time did I see two birds feeding together. The number of crows increased to four as the meal proceeded, but never more than one was busy on the carcass.”

Crows are said to be among the most intelligent of birds, and these instances seem to equate intelligence with caution. They must have been excessively cautious to take four days to dismember the carcass of a squirrel in the dead of winter.

At the tail-end of summer one encounters the usual number of damaged specimens of butterflies eking out their last few days of life. Recently I saw a Small Tortoise-shell butterfly so badly battered that it had only two complete wings left, the rear wings being reduced to tatters. Yet it was consorting with other butterflies of the same species and doubtless managing to mate. A colleague had observed a Peacock butterfly with the whole of one hind wing missing, badly affecting its ability to fly. But this one too had contrived to find a mate.

I am reminded of a series of experiments carried out on caterpillars by which the caterpillars were deprived of their heads with a minimum loss of blood. Being more or less fully grown, they proceeded to pupate and in due course emerged as complete and perfectly healthy butterflies, but without heads! They enjoyed a longer life than normal individuals, being content to sit around in the sunshine instead of wearing themselves out mating!

A Cambridge (Massachusetts) reader tells me the story of a honeymoon couple, recently returned from the Caribbean, who having been given an underwater camera, had difficulty in persuading the fish to pose; whereupon a member of the crew producing an aerosol can containing a disgusting concoction he called Cheez-wiz, saying it was an infallible attraction for fish. And, indeed, it was! The would-be photographer hadn’t even time to take the top off the camera before he became aware of fish swimming his way from all directions!Why the Tick?

by Ralph Whitlock

July/August 2018 Issue

Guardian Weekly, August 9, 1987

The daily grooming of our dog at this season too often reveals the presence of ticks – horrid, bloated creatures, their distended bellies filled almost to bursting with dog’s blood. They must cause the dog intense irritation, as I can testify from experience. When one fastens its jaws into my flesh the little wound stings and torments me for two or three days, even though I take measures to dispose of the pest before it really gets going.

A generally accepted method of ridding a dog of ticks, by gripping the creature between thumbnail and fingernail and pulling, is not to be recommended. The tick is almost sure to break in the wound. Smokers can apply a lighted cigarette to it, which usually causes it to release its grip. I simply smear a well-tried insecticide from a tube on and around it. The tick soon dies and falls off, though the irritation lingers on.

In my time I have quite frequently been persuaded to talk at harvest festivals, flower festivals, and the like. On these occasions I am expected to enlarge on the beauties of Nature, the exuberant song of birds, the exquisite color and texture of flowers, the cornucopia of fruits that

autumn produces, the perfume of bee blossoms, the strength of weather-defying great trees, the marvelous instincts that control the behavior of all living things, and the many other glories of the countryside. I have done so sincerely and to the best of my ability, for the earth is indeed filled with harmony and wonder. And yet, in the recesses of my mind, lurks the spectre of the tick.

Who invented the programmed and miserable little horror? And for what purpose? If it were a killer it would be more comprehensible. After all, the natural order of things is that every living creature survives by eating others whether animal or plant. So we learn to accept the flesh-tearing tools of claw and fang, the venom of snakes, and the knife of the slaughterman. We know that the primary principle in Nature is ruthless competition, in which even beauty is often used as bait for a trap.

At this season I frequently come across crab spiders (I believe their name is Thomisidae), cleverly camouflaged to match the vivid colors of the flower petals amid which they lurk. Beautiful creatures, yet death to the incautious bee or fly which alights for a sip of nectar. Even the apparently static plants of garden and wood are engaged in earnest endeavors to strangle or smother each other, as a speeded-up film of a patch of vegetation during spring and summer clearly reveals.

The tick is not like that. It doesn’t kill; it merely tortures. It can pass on to its host lethal parasites, but that is incidental. And the torture can be decidedly painful. The tick normally goes for sensitive tissues, such as eyelids. I have seen a warbler with a tick bigger than its eye attached to its eyelid. The bird frantically tried to rub it off against a twig.

Naturalist Gerald Durrell has given the lie to the myth attaching to animals enjoying life in the wild. On his numerous expeditions to procure specimens for his zoo he has found that his first task when confronted with a newly captured animal has been to mount a blitz on its assorted lice, fleas, ticks, and other parasites and to treat it for any infections.

I wonder whether that is the ultimate role of mankind in this complex world? To relieve suffering among wild creatures as well as in our domestic animals and in humans. After all, we have now a formidable array of weapons at our disposal, as my mail of press releases from the agrochemical industry amply illustrates.

The ducks and waders and terns that nest on the shores of the Arctic tundra surely deserve success after making their tremendous journeys into those inhospitable climes and assiduously incubating and protecting their eggs and young, especially as the chicks and ducklings are such appealing balls of fluff. Yet those same babies are the natural food of the native skuas and blackbacked gulls which, robbed of their victims, would go hungry. The same considerations apply to all predators and their prey.

How far down the wildlife scale do we take the argument? Those of us who have spent time in India have probably seen holy men there who have such regard for the sanctity of all life that they refrain from cutting and washing their hair in order to protect the lice and fleas which thrive there. These lowly forms of life, they maintain, have as much right to live as they themselves have.

Can that argument be applied to ticks? Am I justified in ridding my dog of an irritating parasite by depriving the tick of its meal? Has the tick the right to as much consideration as the dog? What do you think?

So many times at those harvest and flower festivals I have joined in the singing of the old hymn: “All things bright and beautiful, All creatures great and small, All things wise and wonderful, The Lord God made them all.” Including the tick?

Menus for Hedgehogs

by Ralph Whitlock

May/June 2018 Issue

Guardian Weekly, February 23, 1992

Events have conspired to dictate that the subject for today shall be hedgehogs. I have received no fewer than four letters raising different aspects of hedgehog lore, and then, a few days ago, I found a young hedgehog drowned in our garden pond.

This last was an almost inevitable casualty. More than half of our hedgehog population do not survive their first winter. They belong to a litter born in late September and so are not independent of their mother until November, which doesn’t give them much time to fatten up for hibernation. This one was obviously out searching for food when it should have been asleep. Incidentally it was the only hedgehog I have seen in my garden for more than a year, though that doesn’t necessarily mean that none were there. Hedgehogs, when not pressed for food, are essentially nocturnal.

An American correspondent, reminiscing about his Somerset childhood, says he is familiar with the loud snuffling and grunting that heralded a visit to the back garden by a family of hedgehogs. He and his brother used to hasten to offer them a saucer of milk, which, in spite of the doubts of some naturalists, is an acceptable treat. Hedgehogs will go up to a quarter of a mile for bread-and-milk, guided by smell.

A reader who has recently visited the Hausa and Djerma people of Niger tells me he was surprised to find that they eat hedgehogs. Actually, he says, he was surprised to find one there at all, and inevitably it was squashed in the road, implying that the African hedgehog has about as much road-sense as its British cousin. The natives roast hedgehogs caught well out in the countryside but regard those found in the vicinity of villages as unclean, due to feeding on human waste, and so have a special method of preparation.

They remove the internal organs and head, and then up-end the body directly over the fire and boil it. The “shell” serves as its own cooking-pot, and when the fat is bubbling the organs are returned to the shell, thereby creating a sort of stew. After the stew is eaten the shell itself is consumed, all the spines having by then been burned off.

A nicer part of the story is that the Hausa do not eat “dancing hedgehogs.” When a hedgehog is found, children and women surround it chanting a song, a rough translation of which is “Pithier patter, pitheir” (the local name for the hedgehog) “come dance for us, come dance!” Many animals do sway and move to the rhythm. If so, they are thanked and allowed to go on their way. If not, they are eaten.

My correspondent asks whether I have any English recipes for cooking hedgehogs. The only one I know is the gypsy formula for roasting a hedgehog. You wrap the hedgehog in a thick layer of clay and bury it in a hot fire. When it cools a little, peel off the clay, which takes off all the spines with it. The flesh is revealed as white and very tasty.

A New Zealand reader writes that hedgehogs seem to be one of the few success stories in the disastrous catalogue of the introduction of alien species. Rabbits, goats, pigs, cats, rats – the list is endless – but the hedgehog is the gardener’s and farmer’s friend.

She comments, “In Australia snails and slugs exist in plague proportions, but here we see only a few empty snail shells and the occasional slug in the too-long-unweeded parts of the garden. We are most grateful that we have hedgehogs in the garden.”

She quotes a book with a statement that, as hedgehogs are carnivores, bread-and-milk is entirely the wrong food for them, but my opinion is that the hedgehogs know best.

Finally I have a letter from a reader who lives on an island off the coast of Greece and who writes, “I want to tell you about my dog whose mania was catching hedgehogs. She used to bring them to me at first, never minding the prickles, but when she found I either released them over the wall, if still alive, or disposed of them if dead she took to burying them herself, to mature for her future delectation. I usually managed to find the tell-tale mound and remove the body while she was shut indoors, but sometimes she would stand guard over it all night, growling if I approached, only two green eyes to be seen in the dark.

“The strange thing is that a visitor, a Greek countryman, said immediately on seeing her, ‘That’s a hedgehog dog.’ She was a stray. I can only think that she was descended from a gypsy breed trained to fetch hedgehogs for supper.”

Well, I have met all sorts of dogs in my time, but this is the first “hedgehog dog” I have come across. Have any readers ever encountered one?

A Ringwood (England) reader sends me a query about a word used by his great-grandfather (born 1807). When referring to anyone who had upset him or whom he thought of no account he would call him a “wuzbird” or “woozebird,” but he could never find out what it meant.

Well, I can enlighten him. My father (born 1874) used it occasionally. The word is actually “husbird” or “housebird” and was used in a derogatory sense of a man who was a layabout, staying at home all day and consorting with his neighbours’ wives!

Surrogate Mums of the Farmyard

by Ralph Whitlock

March/April 2018 Issue

Guardian Weekly, April 29, 1990I suppose it must be just coincidence, though to me it sometimes seems uncanny. A reader in some distant corner of the globe sends me a query on some obscure subject which seems worth investigating. But before I have a chance to write anything about it, or even before I have answered his letter, several other letters on exactly the same subject fall on my desk!

For example, back in June a reader in Greece wrote to me on the subject of surrogate mothers in the farmyard. “Twenty to twenty-five years ago,” he told me, “my father had many kinds of birds on his farm – chicken, turkeys, ducks (green-necked mallards), pheasants, even a couple of peacocks. The last-named tended to proliferate to such an extent that our village, near Argos in the Peloponnesos, echoed to the shouting, to the exasperation of our neighbours. We even managed to ‘export’ this displeasure to France, where a friend who acquired some of our peacocks was given an ultimatum by the neighbours – either get rid of them or move elsewhere!

“Have you ever come across cases where hens have been used as surrogate mothers? Ducks and hen peacocks tended to disappear for some weeks and then come back with their hatched broods . . . if they ever did come back. So we used to follow them, or keep them in pens, in order to collect their eggs. When we had enough eggs we used to place them under broody hens, who in due course found themselves in charge of some decidedly strange offspring. Ducklings, of course, used to get the hens really worried, as they fussed around the edge of the pond, clucking and trying to coax the little ducks away from all that dangerous water.”

My correspondent poses a query. “The hens seemed able to change their clucking to appeal to almost every sort of foster-chick, except peacocks. Those never responded at all. I wonder why?” Now that particular query I cannot answer, except to say that I am not surprised at the question, for peacocks rank pretty low in the intelligence stakes. But what intrigued me is that within a week of receiving that letter I had one from Canada, asking whether I remember when broody hens were in strong demand by gamekeepers for hatching pheasant eggs.

And another from an English reader enquiring whether there were any snags about using broody hens to hatch turkey eggs. At the same time a neighbour was successfully acting as surrogate mother to a brood of orphan sparrows. And all coincided with the publication of my book, The Secret Lane, in which on the very first page the hero is sent down to the village to borrow broody hens. “Broody hens were at a premium in March and April. Farmers’ wives wanted them for incubating hens’ eggs; the keeper, Henry Upshot, for sitting on pheasant eggs.”

How do those coincidence arise?

Well, I can answer one of the questions categorically. On no account use broody hens for incubating turkey eggs. Domestic hens carry a whole range of germs to which apparently they have developed some immunity but which are lethal to young turkeys.

We knew nothing of this in the 1920s, when my parents started keeping turkeys with the other farm poultry. We bought turkey eggs in the market, popped them under domestic broody hens for a month and then put them in the orchard with the chicken, ducks, geese and bantams. The mortality rate was always alarming, but we had no idea what the trouble was until the Ministry’s poultry officer enlightened us.

Then we fixed up an old barn loft as a permanent turkey house, placing the day-old poults, purchased from hatcheries, there under infra-red lamps and allowing them to spend their entire lives there. We used then to achieve a survival rate of about 95 percent. Moral – always keep turkeys well away from other poultry from yards or pastures contaminated by poultry. Broody hens as surrogate mothers were satisfactory with most other types of poultry, even ducklings. But trouble sometimes resulted when we inadvertently used a broody hen that had, either in this or a previous year, hatched a normal brood of chicks. She would remember what normal chicks sounded like when they were hatching under her feathers and recognised that these alien ducklings were different. If my mother were not quick enough to rescue them she would peck them to death.

Ducks, of course, are not to be trusted to hatch their own broods. Apart from tending to desert the nest when there are still eggs to be hatched, their instinct is to take their ducklings on marathon cross-country treks on which a mortality rate of 50 percent or more is quite acceptable. Bantams are probably the best of all surrogate mothers and were much in demand.

When I was a small boy Billy Goodrich came to live for a time on the next farm. Billy was a lad of imagination, full of bright ideas. One spring, when demand for broody hens was at a peak and we couldn’t find enough to go round, Billy announced that if you got a cock thoroughly drunk he would serve the purpose equally well. Not for incubating the eggs, of course but for brooding the chicks. I suppose he argued that if the cockerel were too drunk to stand up, he would be glad to sit down anywhere, even on a brood of chicks.

So we picked out one of the biggest and best of our cocks and fed him on mash soaked in whisky till he could hardly stand. Then we sat him in a quiet corner and gave him a brood of chicks to foster. The experiment was a disaster. The pie-eyed cock refused to sit still. He staggered to his feet and went blundering about, scattering baby chicks right and left with his great splayed claws!

I forget how we got out of that one, but I do remember that Billy Goodrich was absent when the explanation time came.

EDITOR'S NOTE: - Here are some observations by Harvey Ussery, Mother Earth News

Using a broody hen to raise your chicks provides several additional benefits to both the chicks and you. The mother forages natural foods, mostly insects, for her chicks, keeps her young ones warm even while ranging on pasture and through cooler weather, and provides devoted protection from predators. The flock-keeper who chooses to foster broodiness (the inclination for a hen to hatch her own eggs) will be rewarded with a healthy, self-sustaining flock.

Modern Breeding vs. Broody Hens

Commercial hybrid breeds lay lots of eggs, but they aren’t a good choice if you want hens that will go broody. In today’s era of mass production of chicks via artificial incubation, broodiness is considered not merely an unnecessary nuisance but an economic calamity. After all, a broody hen ceases laying eggs when she’s incubating eggs and caring for chicks. Thus, a major component of modern poultry breeding has been to select against the broody trait in favor of hens that simply lay their egg per day, having forgotten that doing so has any relation to reproducing the species.

A Dabster For Rats

by Ralph Whitlock

September/October 2017 Issue

Guardian Weekly, April 29, 1990A dog book I have recently acquired, to pass on to my daughter, is All About the Jack Russell Terrier, by Mona Huxham. It is one of a series, “All About Dogs,” breed by breed, published by Pelham Books, but this title attracted me particularly because my daughter’s family dog is a Jack Russell. Roly is as full of character as any little dog I have ever met.

Jack Russells have the interesting distinction of not being recognized as a breed by the Kennel Club. They are officially a strain of terrier, not a breed. And that could well be their salvation. Too often breeders of recognized breeds tend to exaggerate the distinguishing points for show purposes.

Bulldogs, for instance, are a gross caricature of the dynamic animals originally bred for fighting bulls. The Old English Sheepdog has sacrificed skill in handling sheep for a dense coat that would be a handicap in any sheepfold. A sinister development in the Rottweiler is that apparently some breeders are deliberately breeding for aggression. Jack Russells, however, not only have a goodly inheritance of hybrid vigor; they also tend to be bred for intelligence.

One of the most intelligent dogs that have ever shared my life was a mongrel Jack Russell – well, even more mongrel than most. It was also the most celebrated, for at one time it was the best-known dog in Britain.

This was in pre-television days, when my BBC radio Children’s Hour program, Cowleaze Farm, was becoming popular. Parties of children took to visiting my farm, with the statement “This is Cowleaze Farm, isn’t it?” Well, Cowleaze Farm was an imaginary, studio farm, but it was easier to agree with them than to explain. Then came the next question, “Where’s Towser?”

To start with, there wasn’t a Towser, so one day I suggested to my vet, “If ever you get a dog that answers to Towser’s description, you’d better let me have him.” And before long a dog was introduced, a mongrel Jack Russell. It wasn’t even the right sex, being a spayed female, but somehow it seemed more appropriate to call it “he.”

It was eighteen months old, completely neglected and handed in because it was considered hopeless. When given a wicker basket to sleep in, it ate it! It was eager to please but didn’t know how to go about it. More than once we said, “We can’t possibly keep this dog!” But we did, and in due course Towser was loved by millions of children.

From the viewpoint of what was required of a farm dog in those days (the late 1940s), Towser had one supreme qualification. He was a dabster for rats!

Several worthy dogs have shared our home with us since Towser died in the early 1960s, but my thoughts raced back to him the other day when I was reading a paper, published in the current issue of our county Archaeological and Natural History Society, on rats in Wiltshire. The author, Marion Browne, who is a leading authority on mammals, has been conducting a systematic survey of their status from 1975 to 1989. Eventually she collected 453 records, involving a minimum of 1596 rats.

The figures gave me a start. I read them again. Less than 1600 rats in fourteen years. Why, back in Towser’s day we could have accounted for, and probably did, that number in a single winter!

But then I asked myself. When did you last see a rat? I could answer that easily, for I keep daily records of animals and certain insects as well as birds. Checking my charts I found that I saw a rat – and that was a dead one, squashed on a road – on March 21. It was the only one recorded in the first three months of the year.

How very different was the situation on the farm where I was raised. Rats were everywhere. In thatched roofs, in barns, in fields and hedgerows, in ricks – particularly in ricks. The one season when I can be fairly sure of seeing a rat in my garden is autumn, when rodents migrate from the fields and woods in search of winter gardens. Most years at least one will try to take possession of our garden shed, requiring me to call on the services of the council pest officer (alias rodent executive, alias rat-man). In this respect, rat behavior has not changed. The autumnal invasion of the farmyard by rats was a feature of life on our farm, back in pre-war days.

As soon as possible after harvest the peripatetic threshing machine would arrive to thresh a proportion of our corn ricks, to provide my father with enough cash to pay the rent and carry on, but we always left a few ricks for threshing on the machine’s second time round – often in late winter. By that time, the ricks would be alive with rats. You could go out at night with an electric torch and an airgun and shoot them galore as they poked their noses out of holes in the sheaves. The owls grew fat.

Nemesis eventually overtook them on threshing day – the red-letter day of the whole year for Towser. An angel of death, he was everywhere. We could never use a gun for fear of hitting the dog. But he didn’t let many escape.

In her paper Marion Browne quotes an estate in East Anglia where in the year 1906 14,662 rats were killed. Over 10,000 were accounted for in 1926, and 1,500 annually between 1926 and 1942. She comments that there is no reason to suppose that things were different elsewhere in England, and they were certainly paralleled on our farm.

And now, to think that the brown rat has become a comparatively rare animal! I can hardly believe it. It is good that Towser died before he needed to adapt to such a famine. A rodent-free England would have been no place for a dabster for rats!

Apparently the annual tolls remained fairly steady until 1954, when myxomatosis wiped out rabbits. The inference is that foxes and other predators that had lived mainly on rabbits then had to turn their attention to rats.The Pack Instinct

by Ralph Whitlock

May/June 2017 Issue

Guardian Weekly, June 16, 1991

Our ancestors had their own methods of dealing with rampaging dogs. Rain had been falling steadily for the past three hours and looked like continuing for the rest of the day. Water dripped from the tree branches, and every blade of grass sagged under its weight.

“What are those dogs doing there?” asked one of the two woodmen, as they entered the woodland clearing.

What aroused their suspicions was that the dogs were doing nothing. One a big mongrel, of retriever type, the other a much smaller dog, just sat there in the pouring rain. When the men approached, the larger dog roused itself and loped away into the woods with a furtive backward look.

The little dog followed. It did not take the woodmen long to find the part-eaten deer carcass. And the dead kid, a few yards away. The roe deer mother had evidently given birth about two nights previously and, when attacked, had chosen to remain with her baby, paying the inevitable penalty. The dogs had been roaming unaccompanied. Recognizing them, the woodmen called at there owner’s home a mile or two away and found her working in the garden. The dogs returned while they were there. They recognized the mangled carcass the woodmen were carrying and slunk away to hide. Their owner was horrified and apologetic.

Now that suburbia has taken over so much of the English countryside, the bored dog is becoming an increasing problem. In this instance, the tragedy was due to carelessness or irresponsibility. The dogs had simply been allowed to run loose. “But why would they want to do this?” cried their incredulous owner. “They’re always well fed.”

The comment displays a lack of understanding of the nature of a dog. Unlike a cat, which hunts alone, a dog is a social animal. Its instinct is to run with a pack, under a recognized leader. In its relationship with we humans, it accepts its master or mistress as its leader. That is why it is such a good companion.

A farm dog, out and about with its master for most of the day, is one of the happiest animals imaginable. A town dog, confined alone to the house all day while its master and mistress both go out to work, is not. It is bored and frustrated. Its owners are ecstatically greeted when they return in the evening. Having been pent up all day and needing exercise, the dog is ready for what is, for it, the high spot of the day, “going walkies.”

If that happens to coincide with its owner’s mood, that’s fine. But there are inevitably times when the household humans return home too tired, or when rain is pouring down, or on winter evenings when dusk falls by four o’clock. Then the temptation is to open the door and let the dog out to take a run on its own account.

Even when out with its owner, a dog living a town or suburban life needs much more training and control than one which spends most of its time with its master. A dog is naturally more energetic and quicker in its movements than a man – behavior related to its having four legs instead of two. If unchecked, it will go racing ahead, following exciting scents. A dog not trained to come to heel when called may well get carried away by the exhilaration of the chase.

In the incident which prompted these thoughts the victims were deer. They could as easily have been lambs, or geese, or hens. Indeed, it was learned afterwards that the bigger of the two dogs had already been in trouble for killing poultry. And, believe me, once a dog has killed under such circumstances it will do so again, given the chance.

When, more than 20 years ago, we left our farm and went to live in London for a few years, we gave away our farm dogs to neighbors whom we knew would give them the sort of life they were used to. The one dog we took with us to the suburbs was our daughter’s Pekinese, who, we surmised, would be able to cope comfortably with the amount of exercise we would be able to give him. And so it proved. Sam is the fourth Pekinese who has since shared our lives.

Our ancestors had their own methods of dealing with rampaging dogs. On exhibition in the Verderes’ Hall at Lyndhurst, in the New Forest, is a venerable bit of ironwork known as Rufus’s Stirrup. Back in the Middle Ages, this was the device for measuring the size of dogs allowed to be kept by New Forest commoners. If the dog could be squeezed through the Stirrup, measuring ten and a half by seven and a half inches, it was acceptable. If not, it had to have three front claws of its forefeet cut off with a chisel – a process known as expeditation.

Big, mastiff-type dogs, very like the modern Rottweilers, were then popular and were quite capable of pulling down the red deer regarded as royal property. Expeditation effectively put an end to that activity, cruel though the deterrent seems to us.

Somewhere to Sit Down

by Ralph Whitlock

April 2017 Issue

Guardian Weekly, July 13, 1986Aunt Polly has been in my thoughts lately. When I was a small boy she kept the village shop – the first shop, I believe, ever to exist in our small village. Before her bold innovation, villagers had to rely on occasional pedlars or on twice-yearly excursions to the town (2 1/2 hours distant by carrier’s cart), at Easter and Fair Day, for the relatively few commodities, such as Easter bonnets and chemises, which they themselves could not produce.

Aunt Polly (who may not have been my real aunt, but no matter; everyone in our village seemed to be related) lived with her two brothers and an invalid sister and began shopkeeping when the more enterprising of the brothers set up a village bakery. That may have been a new departure, too, for there was a strong tradition of homebaking. I gather that most of the family gave a hand with the baking in the early morning, after which Uriah delivered bread by pony-and-cart to outlying farms and hamlets; Walter trundled a covered barrow around the village; and Polly dispensed loaves to calling customers from her front room.

In due course, the front room became equipped with counter and store shelves, as Aunt Polly widened her range of stock. She could supply candles, paraffin, tea, soap (yellow or Lifebuoy), loaf sugar, matches, black lead, boot polish, pegs and sweets kept in big glass jars in full sunlight.

One of my abiding memories is of going into Aunt Polly’s shop for a ha’peth of peardrops and watching her bite a sweet in half to get the exact weight! The other half went back in the jar. There was, of course, no reason for her to stock eggs, butter and potatoes (you got those from the farms), or boots and bootlaces (they came from the cobbler), or mousetraps (old Billy Medcalf made a type that were more effective than any I have been able to buy since).

It was all very basic and primitive, but I have recently had reason to reflect that in one respect it was streets ahead of the stores and curent supermarkets. It had a chair for customers to sit on. It is true that Aunt Polly’s shop seldom had more than one customer at a time, but that gave a welcome opportunity for a helpful little gossip. Aunt Polly had a chair on her side of the counter, too.

Thursdays are our usual shopping day, but the other week when Thursday came round I was in some agony with fibrositis or sciatica or something of the sort – something I had never experienced before and don’t want to encounter again. With my wife still somewhat incapacitated by her traumatic illness of two years ago, I need to attend her on these shopping expeditions as chauffeur, guide dog and beast of burden.

I rather enjoy indulging myself extravagantly at the food shelves, but in the departments which sell detergents, household goods, cosmetics and kitchen rolls I am bored. (Other husbands, like myself, must have been amazed, amused and finally bemused by the time necessary for buying tights, shampoo of the right mixture, and matching refills for cosmetics!)

And this is when the absence of chairs in modern emporia came painfully to my notice. Here was a new supermarket, covering it seemed to me about six acres, and never a chair, bench or stool for the benefit of weary customers. Even mediaeval monastic churches, addicted though they were to inflicting penance on the flesh, provided misericords for legweary choristers to perch on.

But our supermarket designers are made of sterner stuff. Banks and libraries pander to our weaknesses, some of them even to the extent of supplying upholstered easy chairs, but the staff of supermarkets eye you with disapproval if, in default of anything else, you sit on the stairs.

I sat on the stairs while my wife debated with herself about packets of tights, all of which looked exactly the same to me. A mum with a child in a pushchair sank wearily on the step below. “They put all the everyday household things upstairs,” she lamented. She even accepted my offer to look after the child while she went up higher, though perhaps I don’t look like a kidnapper!

“I just can’t do it,” said an elderly sufferer, joining us on the stairs. “I have a bit of a rest and then go elsewhere. It’s another of these American ideas, isn’t it?”

And that’s the odd thing about it all. Supermarkets are, I believe, an American idea, but virtually every American and Canadian supermarket I have ever patronised has those basic facilities which ours lack. They have coffee shops or restaurants; and well-equipped toilets where a baby’s nappy can be changed; and a trolley park where the shopping can be left until the shopper is ready to go to the car.

Where the stores are on more than one level escalators are universal, but if they were not I feel sure that assistants would be on hand to help mothers with pushchairs upstairs. The only way you can attract the attention of staff in a British supermarket is to try a bit of ostentatious shoplifting.

Come back, Aunt Polly, you would be welcome to half my pear-drop in return for a hard-bottomed chair to take the weight off my feet.

There is one remedy for these glaring deficiencies in service to the customer. It is a planning application for a new hypermarket. Hypermarkets have a reputation for providing all the missing amenities, including a spacious car park, well outside the town limits.

At the very hint of a new one coming their way, all the town traders unite in a protest campaign. They argue, rightly, that if the plans come to fruition they stand to lose customers. And serve them right. They should look after their customers better, while they still have them. Even to the extent of offering them a few chairs.The Dog That Eats Plastic

by Ralph Whitlock

November/December 2016 issue

Guardian Weekly

October 23, 1994

About Ralph Whitlock

Over the past two months my correspondence has yielded a larger than usual crop of tales of animal eccentricities.

There is Biggles, a dog in Sarawak, who has unaccountably developed a liking for plastic number plates. His master emphasizes that he actually eats them, not just chewing and discarding them. Honda and Datsun plates are his favorites, and the household Honda has to be protected by a temporary brick wall. A sprinkling of chili powder on the number plate did nothing to deter this pooch, who, indeed, seemed to relish it. Now the dog has started on a plastic doormat.

I have told my correspondent how lucky he is! Ecologists are at their wits’ end to deal with the ever-increasing mountains of “non-biodegradable” plastic . . . and out there in Sarawak is an organism which can apparently digest it. I recommended his master to take good care of Biggles. He may represent a fortune!

Do animals have a sense of humor? A New Hampshire reader is sure they do. He quotes the instance of a favorite cow of an old friend of his who, from time to time, when being milked, would bring her head round, very slowly, and slip a horn under his belt. She would then lift him off the milking stool and gently bring him round to the front. He used to swear (literally) that she had an expression of enjoyment on her face.

My own experience in that connection is of cows putting a hoof in the bucket when they were being milked. On such occasions I haven’t studied the expression on their face, but I believe they did it deliberately.

By the way, another reader remembers the milkman who used to deliver milk to the door from a churn in his boyhood days in Lincolnshire. Capping my recent story of the farmer (of sixty years ago) who strained milk through his shirtfront, this reader recalls when his mother complained, “Yesterday’s milk was a funny color.” “Aye, it were a bit,” admitted the milkman, “though I strained it well after the cow put her foot in the bucket.”

Very different is the story of Purley, a dog whose mistress lives in an Arctic town in Yukon. She writes, “Recently a circus with animals came to town, and, driving from town, we encountered elephants standing outside a circus tent. Purley did not bark nor show any agitations. She absolutely refused to look at them or acknowledge their presence in any way. I remember that a year or two ago she reacted in the same way to a bear we saw when we were camping. She also ignores her own reflection in a mirror, and I wonder whether by the same reasoning?”

Purley’s reaction to her image in the mirror is not parallel to the other two instances. She has doubtless seen it many times. It lacks the one essential by which dogs identify details of their environment, namely, smell. Sam, our Pekingese, is quite indifferent to his mirror reflection. To animals on the television screen he reacts mildly, especially if they are noisy or lively, but for him something (scent) is lacking and he quickly loses interest.

With the elephants and the bear, of course, the situation is quite different. The dog would certainly have been able to smell them. Her rejection of them would therefore seem to have been deliberate. They were so far outside her normal range of experience that she didn’t know what to make of them. Best to pretend they weren’t there!

That that was the correct explanation seems confirmed by an account I read, not long ago, of Columbus’s early voyages to the West Indies. When he introduced the first horses to the islands he was amazed by the reactions of the Arawak Indians. They refused to show any interest in these strange animals, even to look at them. They were so far removed from anything in their experience that they had no idea how to come to terms with them. Best to pretend they didn’t exist! (Mind you, it wasn’t long before they had to change their minds.)

An unlikely creature to exhibit eccentricity was a New England grouse, about whom a reader tells me. For three successive seasons of seven or eight months each “he would appear while we were preparing the gliders for flight and spend most of the day with us. If one of us left prematurely (in his opinion) he would run after the offender and peck at his ankles. Ultimately he allowed the glider owner to pick him up, which led to him appearing in a film, answering questions with a sort of burble, after the manner of grouse. I must emphasise that he wasn’t coaxed by being fed or suborned in any other way.”

In the fourth season he failed to turn up, but three years is quite a good age for a grouse in the wild.

My final example of eccentricity is on the part of the guardians of animals rather than of the animals themselves. In a fascinating letter about life in Arkadia, in southern Greece, my informant tells me of the shepherds who in winter keep their flocks under the olive and orange groves by the sea and in the spring escort them gradually up through pine forests to the mountain pastures.

When he came to live here he was very surprised to find the shepherds collecting mistletoe from the pine trees to feed to the sheep. Like myself, he had thought that mistletoe was about as poisonous as yew, but the shepherds assured him that it made the sheep give more milk!Elephants are Human

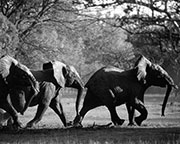

by Ralph Whitlock

July/August 2016 issue

Guardian Weekly

October 23, 1994About Ralph Whitlock

First, two elephant stories, one from Tanzania, the other from a lady who lives in Seychelles but who took a holiday in Kenya. Both reveal a degree of intelligence on the part of elephants, and, indeed, of compassion.

The Tanzanian one concerns a party travelling to Dar es Salaam who found themselves passing through a forest named the Forest of the Elephants: “There we saw many animals – hippos soaking in the streams and zebras moving amongst the trees. The most plentiful and noticeable, however, were the elephants of which we must have seen more than 100, all in small groups, of two to five.“We saw, near the road, a dark-green mango tree, full of fruit. Five elephants surrounded it. They would grab a branch of the tree with their trunks and shake it and shake it until the mangoes, both ripe ones and green ones, fell off. It seemed to us they were playing as they ate. They circled the tree and wove their trunks up into its branches, shaking them hard enough to release the fruits but not hard enough to break the branches.

“When the mangoes dropped, all the elephants rushed forward and, with much pushing and shoving, grabbed them one by one, and ate them as fast as they could.

“But one of the five elephants was a small one, and, with all the pushing and shoving, he didn’t get any fruit at all. He became frustrated and increasingly angry. Eventually, he went up to the mango tree and began to push against it.

“He worked himself into such a fury that the older elephants took notice and went over to the tree. They put their bodies between him and the tree and then herded the young one away, as if to say, ‘That’s not proper’.

“When he had calmed down, they shook the tree again and allowed the young one to pick up the mangoes.”

The second story comes from a reader who was spending a night at Treetops in the Aberdare National Park, Kenya. They missed seeing lions on this occasion but enjoyed watching the antics of several herds of elephants at the waterhole . . .

“Shortly afterwards we noticed four hyenas who were surreptitiously separating a young buffalo from its herd. The buffalo herd had begun to wander off slowly, one by one, leaving the youngest of them alone. The hyenas had obviously become aware of this situation and were keeping watch.

“After some 10 minutes or so of strategic maneuvering, the young buffalo began to react nervously, suddenly becoming aware of its plight. By this time, though, there was little it could do to escape.

“Suddenly we were startled by a chorus of trumpeting from several elephants who had evidently been watching the unfolding of the drama. Their cries deafened us momentarily.

“The elephants, young and old, charged at the hyenas and chased them away, leaving behind a rather bewildered young buffalo who had little appreciation of his narrow escape.”

This is a rather remarkable instance of animals of one species coming to the rescue of another animal of a different species.

To conclude, a tender story of love between two wallabies in the Australian bush.

“A male had been drinking at the water’s edge when another approached. Both reared into fighting posture, but the intruder thought better of it and hopped awkwardly sideways into the shelter of some trees. The other male settled down into a wary posture, waiting a renewal of hostilities.

“Then out of the trees came another wallaby, a doe. She approached the buck with assured hops and he rose. For a moment they stood looking at each other; then fell into each other’s arms.

“For at least a minute each caressed the other’s head and neck with gently moving forepaws, until at last, reluctantly, she drew away to drink . . . It was a glorious sight of affection in the animal kingdom.”

A Cat-and-Dog Life

by Ralph Whitlock

May/June 2016 issue

Guardian Weekly

August 14, 1988About Ralph Whitlock

I was pleased to see that my son-in-law, flat on his back in bed with what the doctor had tentatively diagnosed as a slipped disc, did not lack company. Supine on the bedcover and as close to his master as he could get, lay Roly, the Jack Russell terrier. Stretched out alongside him and therefore manifestly the same size, Tommy, the ginger cat, was equally enjoying the novel experience of finding the head of the house in bed in the middle of the afternoon. (My daughter’s family are not very imaginative when it comes to choosing names for their pets.)

But Tommy was busy. Relaxed though he was, he had his front paws, talons half-extended, firmly holding Roly in position while he gave him a good grooming. His rough tongue explored every square inch of dog – tummy, legs, throat, face – while Roly, apparantly hypnotized, lay perfectly still lest he should interrupt the performance.

And these, I reminded myself, were animals which, when they first met as kitten and puppy, some eighteen months ago, had panicked at the sight of each other. Tommy, the first to arrive in his new home, had only a few weeks to become accustomed to it before the introduction of Roly had sent him into a paroxysm of glaring, spitting fear. Roly, for his part, had never seen animals other than his mother and brothers and sisters and cowered before the apparition.

Of course, the relationship between the two soon took its normal course. Roly, a dynamo of energy, instinctively chased Tommy as soon as he ran away. And Tom-my quickly discovered that he had only to jump on a chair to be out of the dog’s reach.

And food was an early bond between them. The cat was soon investigating the dog’s dish, to see whether he had anything better than he had been offered, and vice versa. Before long they were sharing meals. And now they are almost inseparable.

Recently I happen to have been re-reading that delightful book of Derek Tangye’s, A Cat in the Window. Although written as long ago as 1962, it is eternally fresh. Monty, a ginger of evidently the same calibre as Tommy and described by a visiting fireman as “the handsomest cat I ever saw,” dominated the household, first in a London suburb and then in Cornwall. But Derek, a novice at first in the art of handling a cat, admits of two mistakes, which you or I, ex-perts that we are, would never have made.

It was, in fact, his wife Jeannie who was at fault, and she should have known better. Retreating from London to her mother’s country home during the Blitz, she decided that as Monty and her mother’s terrier were to share a home, the sooner they became acquainted the better and accordingly put them together in a room. The result was predictable. The dog gave immediate chase, and the cat, scratching severely a human who tried to stop him and knocking over a table and vase, scaled some Velvet curtains and sat snarling. The two animals never got over the disastrous start. They never learned to tolerate each other.

Then, when the family moved to Cornwall, Derek and Jeannie were concerned lest the cat should disappear and make his way back to London. Jeannie, following an old country recipe, buttered his paws. It was quite necessary. Monty was so mistrustful of the outer world that for a time he refused to go outside the cottage. Derek used to carry him a hundred yards or so, hoping he would become interested in the strange sights and scents, but as soon as he put him down the cat streaked back to the cottage.

You and I, of course, would know that this is normal behavior. Finding them-selves in unfamiliar surroundings, almost any animal will take its time. For days it will sit or cower and observe. When it has decided that this is to be its home it will gradually make a few sorties, making sure that it knows the way back. Eventually it will explore every square inch of what it now regards as its territory, and if it is a male it will fight to exclude any rival claimants. As indeed the terrier did to Monty. The cat was an intruder, to be chased away, and the cat appreciated its unwelcome status and never settled down.

There are, however, exceptions. Consider the case of Dandy and Tiddles.

Tiddles was our own cat, years ago and when the time came for us to move house we decided to leave her for the new owners, who were pleased to have her. They were bringing their spaniel dog, Dandy, with them, but we based our optimism on the knowledge that Tiddles had been used to sharing her home with a dog and that Dandy had done so with a cat, so we hoped for the best. And our hopes were fulfilled. There was no real friction at all.

When the new arrangement had been in progress for about a fortnight, however, a big boxer dog from next door appeared in the garden and pitched into Dandy. The commotion sent his mistress hurrying to the garden, but the cat was first. Without delay she launched herself at the intruder and landed a spitting, clawing fury, on his back. The boxer hastily broke off the encounter and disappeared, never to enter the garden again.

I can imagine Tommy coming to the rescue of Roly if it were to be attacked like that, but how strange that Tiddles should feel protective towards a dog she had known for less than a fortnight!

Say 'Cheese!'

by Ralph Whitlock

March/April 2016 issue

Guardian Weekly

1992About Ralph Whitlock

A strange story comes to me from an expatriate who writes from a small city on the banks of the Yangtse River in central China. He says: “As the Chinese are not great animal lovers (except for edible ones), I take some pride in feeding a family of small brown mice who have lived in my flat for the past year. I sometimes leave small niblets of food out for them and enjoy watching their antics. Usually I gave them fruit or biscuits, both of which are consumed with relish.

"China is completely devoid of dairy produce. Butter and cheese are unobtainable. So, recently somebody sent me some Cheddar cheese from Britain as a treat. Most people here who have studied the English language have heard of cheese, as it’s often mentioned in their textbooks. So we had a party – small cheese-eating ceremony. Nobody liked it at all! In fact, most people found it positively disgusting.

"But what surprised me was that the mice showed the same reaction. They continued to eat the apples and biscuits, even eating raw ginger, but refused to touch the cheese! I always believed that mice and cheese go together automatically, like Italians and pasta, but apparently not. Is cheese so much an acquired taste?"

Yes, cheese is an acquired taste. I have a friend who was reared in a non-cheese-eating household, and it has taken him nearly 20 years of married life to acquire a liking for it. And, in fact, most foods are an acquired taste. When I was in India at a time of famine I had to cope with a reluctance on the part of starving people to eat a cargo of wheat which had been inadvertently delivered to them instead of their familiar rice. They needed a lot of persuasion to try it.

But that mice should refuse to eat cheese opens a wide door for speculation. One would have thought that their instinct would have told them it was edible. [January 19, 1992 Guardian Weekly]My recent story of mice in China which refused to eat cheese has intrigued a lot of readers and produced a number of parallel instances. A correspondent who lives in Kerala, in the extreme south of India, writes: “As you may know, here the coconut reigns supreme and is used daily in cooking in one form or another. When we moved here from Delhi, in the north, where wheat is the staple diet, and found that we were visited nightly by rats, I tried laying a trap with a ball of wheat flour and water as bait. This I would have done in Delhi with assured success, but there were no takers. I then tried with cheese – something of a luxury in these parts – but with the same result. Then I hit upon the idea of using a piece of coconut as bait and caught a rat almost nightly. I noticed, too, that the rats here like soap, presumably because when a coconut goes slightly rancid it tastes like soap! It appears from this and from what your reader living in China says, that rats and mice, quite logically, acquire the gastronomic tastes of the people they live among.”

And a letter from an island in the Greek archipelago: “Cats on Greek islands don’t drink milk! That is, they can be trained to do so, but they don’t do it naturally. Their main joy is fish, and they will pass by a bowl of milk and drink water. Mine, however, have now learned to drink evaporated milk, and the strays I feed will down dried milk, properly prepared, quite happily.”

Reverting to the dislike of the Chinese for cheese, a Canadian reader writes that “a Chinese friend who came to live with my family while she was a graduate student at our university found cheese so horrible that she couldn’t even sit at the table when cheese arrived but found an excuse to go elsewhere. Six months later, however, she had become very fond of cheese.”

Incidentally, he adds, there is milk in almost every milk food store in China but in the form of powdered milk, usually thought of as infant food. There are some Chinese recipes for yoghurt, and, as for cheese, in Chungking one of the popular local dishes is slices of goat cheese, fried. He finds it interesting that the words for milk, cheese, and butter are common words in everyday speech, and yet there is no familiarity with those things.

It is not only animals that become adapted to strange foodstuffs. Humans can be just as adaptable. A French reader writes: “I do not eat a lot of potatoes but lots of chestnuts. I gather about 100 pounds of them in autumn and, stored in a dry place, they last till next autumn. I cook them in boiling water when peeled, mash them with salt, herbs, and a drop of olive oil. To me chestnut mash is far superior to mashed potatoes.” [March 22, 1992 Guardian Weekly]Letters continue to arrive concerning the odd tastes of mice and rats, which began with the revelation that Chinese mice do not like cheese. An Australian reader writes: “While enjoying a hot spring in Barcelona one year, I sought to satisfy my addiction to very hot food. I bought a kebab from a small pavement stall and, as is my habit, requested generous additional lashings of chili sauce.

Being famished, I tucked into it greedily where I stood, the fiery sauce dripping from the end of my pita bread. Next to the stall, besides where I stood, was a large stone trough filled with flowers. To my surprise, a small mouse emerged from beneath the trough and began to feed on the little puddle of chili sauce that was collecting in front of my boot. The audacity of the little fellow was almost as remarkable as the sight of it feeding on what was quite clearly tear-jerking stuff.

The kebab was excellent, so I ordered and ate a second. Sure enough, the mouse reemerged to join me. Despite my own predilection for hot food I was fascinated that the animal could comfortably consume the equivalent of a pint or two of tabasco! It was, from the shine on its coat, a very healthy specimen, too.”

And from Barbados a letter: “The cats keep the rats down, but the mice are cleverer than they. One has lived in the top of the gas stove for years. He appears, all two inches of him, in the gap by one of the burners to collect items left over from the supper of the cats and dogs. Another lies in my closet and drives the cat mad. A frantic scrambling the other morning at about five o’clock denoted their latest battle. When I put on my long trousers, three hours later, the mouse hopped out of them, none the worse for wear, and returned to his closet castle.”

A Dorset reader thinks that this snippet of country wisdom will amuse me: “If you can sit on the earth with your trousers down and it feels comfortable, sow your barley and it will be up in three days!”

Yes, I not only know the saying but I once knew an old farmer who put it into practice! Every year. And I appreciate the wisdom of a carter who, instructing a novice in the art of dung-spurling, cautioned him, “Don’t ee throw it into the wind, mind!” [May 24, 1992 Guardian Weekly]

Lodging for the Night

by Ralph Whitlock

January/February 2016 issue

Guardian Weekly

January 22, 1989About Ralph WhitlockThe north wind doth blow,

and we shall have snow,

And what will the robin do then, poor thing?

He’ll sit in the barn,

and keep himself warm,

And hide his head under his wing, poor thing.

Photo © Matthew Williams I found it easy to remember this rhyme, one of the first I ever learnt, because it corresponded so precisely with what I could observe when toddling around my father’s farmyard. Not more than twenty steps took me across to the big thatched barn, one end of which was the carthorse stable with a loft above it. Here throughout the winter, Kit, Pleasant, and Colonel bedded down comfortably at night, their needs assiduously attended to by George the carter who dropped in at nine o’clock every evening “to rack up the horses.”

Our dogs slept in the kichen, but the cats were put out at night to fend for themselves, which was never a hardship for them. In summer, nights were the best time for hunting, but on wild, cold nights in winter they simply trotted over to the stable and curled up in the horses’ mangers. There, in spring, they often produced their kittens.

The other regular denizen of the barn was the farmyard robin. By the day I often saw him perched on the stable half-door, and at nights he had his favorite roosting-perches, one of them the hames of the horses’ harness. He seemed to have arrived at an understanding with the cats, though dependent on constant, bright-eyed watchfulness on his part. And doubtless he chose his perches well.

By day good pickings were always to be had in the mangers, in the droppings on the stable floor and outside on the dung heap, where scratching hens exposed insect life. From time to time, he came round to the back door, to investigate the cat’s saucer, and he never missed an opportunity for attaching himself to a gardener. It was, in short, a paradisical life for a robin. He had everything a little bird could need – a plentiful food supply and shelter from winter storms.